- Jahrgang 67 (2022), Ausgabe 2

- Vol. 67 (2022), Nr. 2

- >

- Seiten 181 - 198

- pp. 181 - 198

- Zurück

“It will be a thing of Joy and Beauty”: Angel Symbolism in "The Brownies’ Book" (1920-1921):

Abstract

This essay examines the strategic use of photographs in "The Brownies’ Book", the first magazine for, about, and (partly) by African American children. Edited by W. E. B. Du Bois, Augustus Granville Dill, and Jessie Fauset, "The Brownies’ Book" ("TBB") appeared between January 1920 and December 1921. Designed specifically to counter the demeaning depictions of African Americans (both visual and textual) that commonly circulated U.S. mainstream culture at the time, "TBB" made a particular effort to represent their audience in a positive and empowering light. In close readings of two cover images that depict Black children as angels, I will interrogate the politics and poetics of photography in "The Brownies’ Book". I argue that to combat racism "TBB" strategically transforms the figure of the angelic child, a staple of the nineteenth-century sentimental novel and White by default. Idealizing the Black child as an angel, "TBB" challenges White hegemonic use of angel iconography by marshaling composition, style, form, and technological process. As a result, "TBB"’s trailblazing iconographic intervention did help to visually afford innocence to Black children but failed to establish the Black child-angel as an emblem of racial uplift. In today’s visual register it emblematizes, instead, the innocent "victim".

Key Words:"The Brownies’ Book"; photography; children’s magazine; angel symbolism; #BlackLivesMatter

In a 1920 essay entitled “The Immortal Child,”1 American social scientist W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963) stated, “All our problems center in the child,” and “all our hopes, our dreams are for our children” (Darkwater 212-13). Convinced that “children are the future” (212), he advised in another text what he believed was the supreme means to combat racism and create a better future: “the Training of Children, black even as white” (4). In that same year, Du Bois (with Jessie Fauset, literary editor of The Crisis, and business manager Augustus Granville Dill) launched The Brownies’ Book (TBB), a magazine specifically for, about, and (partly) by African American children.2 DuBois would later write in his autobiography that TBB became “one effort toward which I look back with infinite satisfaction” (Dusk 136). Today, scholars unanimously praise what Du Bois himself thought was “really a beautiful publication” (136). Valerie Williams-Sanchez considers it “a thoughtfully crafted artifact that was a cornerstone in the radical reformation of an emergent social class known as the “New Negro” (3). Christina Schäffer finds it “a harbinger of the Harlem Renaissance which helped to shape the movement rather than be shaped by it” (439), with “each issue of The Brownies’ Book [being] an autonomous piece of art” (450). Patricia Young applauds the technical finesse as “TBB was produced using some of the latest print technology of its time. It incorporated text, photographs, sketches, and color tints at a time in history when technological ingenuity was not associated with African Americans” (2). Shawn Leigh Alexander writes of TBB:

In the hands of Fauset’s “capacious aesthetic” children read about black history, were whisked away to fantastic worlds of fairy tales, encountered religious worlds that engaged the occult, and found news snippets of world affairs. The work of young writers graced the pages of The Brownies’ Book and, in a move reminiscent of The Crisis, artwork and illustrations struck the imaginations of the magazine’s young readers. Ultimately, the superlative efforts behind The Brownies’ Book, not unlike The Crisis’ efforts for adults, inculcated young readers with a sense of dignity, place, imagination, and personhood often denied to them in the world of the early twentieth century. (11)

The Brownies’ Book appeared as a monthly periodical between January 1920 and December 1921, and made a particular effort to represent African Americans in a positive light to counter the grotesque stereotypes circulating within U.S. mainstream culture at the time. Addressing all “Kiddies from Six to Sixteen” but especially “ours, ‘the Children of the Sun,’” TBB aimed to empower and promote racial pride in its readers.3 In “The True Brownies,” the October 1919 editorial of The Crisis, Du Bois announces that TBB “seeks to teach Universal Love and Brotherhood for all little folk—black and brown and yellow and white” (286).

To the social scientist it is imperative that “we are and must be interested in our children above all else, if we love our race and humanity” (Du Bois, “The True Brownies” 285). Yet the ramifications of his conceptualizing children “as active social participants” remain yet to be fully investigated (Smith, “Childhood” 799).4 Only in the field of children’s literature—somewhat sequestered away in a special interest section for female scholars—has the “fact” that “the renowned intellectual […] devoted his time and attention to the younger generation and their education” not been “greatly neglected” (Schäffer 447). Children’s literature researchers have long argued for the general relevance and impact of TBB, warranting further research on Du Bois’s political and artistic investment in “the child.”

Violet J. Harris, for example, attests to “the radical nature of The Brownies’ Book” due to its being “deliberately and overtly political” (45). Dianne Johnson considers TBB “progressive in terms of promoting a diasporic frame of reference” (10). Her paean of praise continues: “It is not an overstatement to say that the very existence of The Brownies’ Book precipitated the development of the body of work now called African American children’s literature, in all its subsequent manifestations and meanings” (37). Michelle H. Phillips agrees that “Du Bois’s intervention in the arena of children’s literature is historically remarkable” (590). In 2001, Kory Fern highlights Du Bois’s knack for fairy tales (91). In The Dark Fantastic, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas extends Fern’s claim, conceding that TBB is “a predecessor to Afrofuturism and other forms of Black speculation” (Oeur).

Through close readings of magazine covers depicting Black children as angels, I will interrogate the politics and poetics of photography in TBB,5 thus tying in with Amy Helene Kirschke, who finds that visual imagery is “integral to [Du Bois’s] political program” (49), and Julie Taylor, who surmises that “the sophisticated use of photography” in The Crisis and TBB “provides African American children with access to a cult of childhood that would allow them to be recognized as precious and vulnerable” (747). More precisely, I claim that, to combat racism, TBB strategically transforms the figure of the angelic child, a staple of the nineteenth-century sentimental novel and White by default. Idealizing the Black child as an angel, TBB formally challenges the White hegemonic use of angel iconography by marshaling composition, style, form, and technological process. TBB’s trailblazing iconographic intervention did, in fact, help to visually afford innocence to Black children but failed to establish the Black child-angel as an emblem of racial uplift. In today’s visual register it instead emblematizes the innocent victim.

Compared, for example, with Aaron Douglas’s Art-Deco-style covers of The Crisis, TBB’s angel covers appear as nostalgic reinvocations of nineteenth-century sentimentalism. I will show, however, that they also employ modernist visual aesthetics to simultaneously signify (in Henry Louis Gates’s sense of the term) anachronistic Victorian-age iconography while offering the visually idealized child as a role model to “the magazine’s central reader and protagonist, the youngest of New Negroes, who will bear the mantle of change” (Smith, Children’s Literature xiii). The angel covers encapsulate TBB’s politicization of children in modernist stylistic bravado whose impact on the Harlem Renaissance Williams-Sanchez poignantly describes: “Articulate and egalitarian, the images in TBB sought not simply to innovate, but rather to incorporate, carry forward, and impact the visual language of the emerging ‘New Negro’ into a visual linguistic expression” (18). The visual linguistics remain operative to this day in the antiracist campaigns of the Black Lives Matter movement.

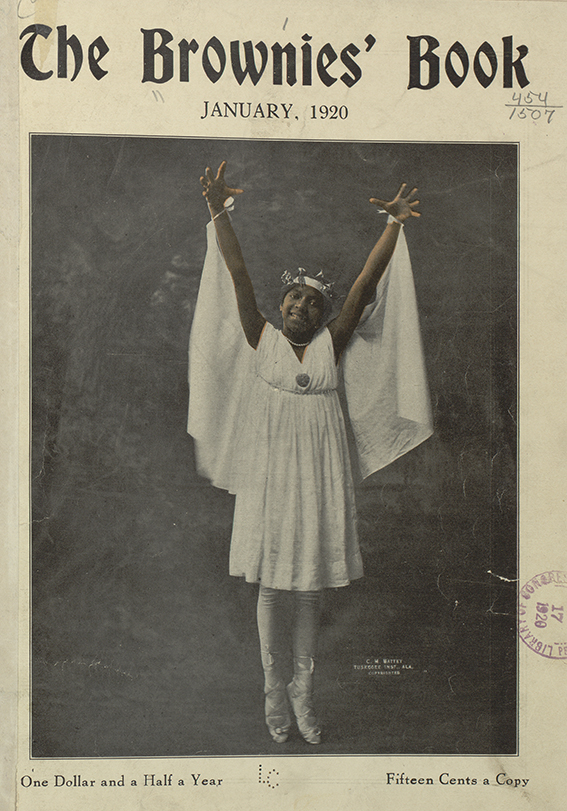

Little Swan, Black Angel

In TBB, “visual representations took the form of sketches, photographs, colored illustrations, and tinted photography,” Young explains. “Cover pages contained images of Black children or Black art” (11). Angels appear on several covers of TBB, most prominently on the inaugural January 1920 issue (Figure 1). It features a Black girl in ballet clothes who looks like an angel, representing “in several ways the epitome of a Western ideal” as Dianne Johnson explains (20). Everything about her “is white, from her soul to her costume” (20). Johnson waves aside the notion that the reproduction of Cornelius Marion Battey’s photograph on TBB’s cover depicts assimilationist desire: “An angel, regardless of his or her adornment, is just that—an angel, and therefore a being who stands in a special relationship to God” (21). To Johnson, only this relationship counts along with its symbolic meaning: “What is indicated is goodness, purity, and the striving towards an ideal. It cannot be assumed simply that whiteness is associated automatically with these qualities in every context and always in direct opposition to blackness” (21).

Yet, since William Wordsworth and “hosts of other writers inflated the angelic child into a kind of saviour” (Wood 117), the epitomal figure of innocence in the Victorian Christian tool-kit codified Whiteness as both the icon and the medium for the soul’s “special relationship with God” (117). The “centrality of whiteness in Western visual culture,” as Coco Fusco summarizes the central idea of Richard Dyer’s White, “depends on Christian ideas about incarnation and embodiment, specifically the notion that white people are more than bodies” (36; emphasis in original). In contrast, Black people are often demeaned as nothing but bodies. Angels stand in for the assumption that “what made whites special as a race was their non-physical, spiritual indeed ethereal qualities” (Dyer 127).

Launching TBB’s inaugural issue with the visual fanfare of a Black child-angel on the cover was thus a bold move in the 1920s United States, where “it was a standing rule that no Negro portrait was to appear” (Du Bois, Dusk 136). The image can be read as assimilationist, as Johnson does, or characteristic of Du Bois’s agenda of “uplift suasion,” which in turn upsets a contemporary like Kendi as “not only racist” but also “impossible for Blacks to execute” (Stamped 125). And yet, one might also argue in favor of the image’s complex antiracist message. Its angel iconography seeks to assert African American equality, but by signifying upon an iconography that functions to naturalize White supremacy, TBB not only asserted Black children’s humanity, it also exposed what is “human and humanly flawed” in everyone (Stamped 125).

Figure 1. Cover page of The Brownies’ Book January 1920, Online Image. Library of Congress, From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Downloaded March 17, 2021. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=rbc3&fileName=rbc0001_2004ser01351page.db.

“Never before had a magazine for children shown a beautiful black child on its cover or even evoked the association of a black child being an angel” (Schäffer 60). A synecdoche for all the other children featured in the magazine, the African American child angel on TBB’s first cover was as revolutionary as it would become programmatic. I agree with Johnson that the image exemplifies exactly the qualities of angel iconography: purity, spirituality, cleanliness, virtue, along with beauty and goodness. Captured with her arms raised high above her head and slightly forward, her fingers spread with palms turned toward the camera, the girl, quite literally, seems about to reach out and claim these qualities for herself.

Wearing a spiked crown—a material substitute for an angel’s translucent halo as well as a signifier of wealth and power like the pearl necklace and brooch she also wears—the girl also mimics the Statue of Liberty. With open arms, she welcomes the magazine’s young readers to enter TBB’s “golden door” and experience uplift and liberation, and the readers are cast as “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” (Lazarus) as TBB invites them to pursue freedom and happiness in their own country.

Lastly, the girl is presented in the role of the little swan. En pointe with her arms in ballet’s fifth arm positions, she gleefully smiles into the camera, signaling pride, ambition, even triumph. Because the little ballerina is not yet trained to perfection, her hand position does not look graceful (nor truly welcoming), a childish mishap for sure but also a suggestive photographic detail that complicates TBB’s visual message on several levels.

The cover image references Du Bois’s concept of training, aiming to groom the young into a “carefully bred, selected, and trained elite” representative of the “‘New’ Negro who will succeed in the modern world” (English 44).6 Advertising the benefits of training, the cover image of the young ballerina opposes racist views of Black inferiority that allegedly results from biological difference. Such pseudoscientific claims circulated freely in the 1920s, prompting so-called experts to voice outrageous assumptions. “John Martin who became America’s first major dance critic when he joined the New York Times in 1927,” for example, “reasoned that for Blacks, the ability to dance was ‘intrinsic’ and ‘innate.’ They had natural ‘racial rhythm,’ and struggled to learn the more technical dance styles, such as ballet” (Kendi, Stamped 327). The cover puts TBB’s mission to counter such defamatory nonsense into visual terms. Given a chance and the support, it says, this girl is as apt as any amateur to finesse her technique by continually practicing as she grows up, because any child regardless of the color of her skin can excel in that to which she devotes her time and talent. This message is brought across by the photograph’s signifying upon the performance of Whiteness.

Dressed up in full ballet attire with a white cape that looks like wings and a crown just like the Statue of Liberty, the girl on the cover is staged ostentatiously as liberty goddess, angel, and ballerina simultaneously. She mimics the figure of the ideal White woman who is herself constructed as “translucent, incorporeal” in “the Romantic ballet,” as she weightlessly dances on the tips of her toes (Dyer 130-31). The cover girl’s aspirational foray into a cultural sphere that is open exclusively for slender White women commissioned to construct nothing less than angelic Whiteness was an affront in the 1920s United States, excusable only due to the child’s gender and young age.

Forgiven or not, the color line had been crossed so that the child’s (adorable) plumpness and masquerade ironically play on the ballerina on stage. Such irony exposes her iconic Whiteness as a performance, too, as nothing but the result of more rigorous training. Even more revealing in this regard is the girl’s botched hand position, a clawing gesture which, intentional or not, disrupts the ballerina’s picture-perfect performance. The intervention is bold because the ethereal Whiteness constructed by Romantic ballet is revealed as substantial, corporeal, and racialized. Once Whiteness is seen as a racial performance, though, it can no longer “function as a human norm” (Dyer 1), and Blackness, in turn, can no longer be considered an aberrance. With visual semantics thus challenged, habitual signification is suspended. The girl on the cover is not seen only as Black. Liberated from the specter of racialization, she can simply be a child who loves ballet.7

There are more technical aspects to be mentioned which support the image’s subversion of iconic Whiteness. First of all, the portrait performs what Dyer, on a different account, calls a mobilization of “the polarity between black and white” (116). The girl is photographed against a studio backdrop that is almost completely black except for the shimmering contours of a tree and wild growths, suggesting a landscape painting of the American wilderness. Her white attire, placed at the center of the image, shines brightly. This is a typical effect of “chiaroscuro,” which is “a key feature of the representation of whiteness” (115). The white dress and the black backdrop are further contrasted with the girl’s brown skin. According to graphic design scholar Anne Galperin, the cover is “an instance of two-color printing. First, the plate with black ink (for the image in greyscale and the type), then another plate carefully registered with just the girl’s arms and face in a second color of ink,” which “is a bit out of registration as seen at the armhole of her dress on the left.” The digitally archived copy of TBB suggests, as Galperin explains in an email conversation with the author, that the cover image was “processed as a halftone,” and that the cover was likely “printed on a smaller letterpress (older technology for that time) and the interior of the magazine offset printed.”

In other words, the cover image was printed with the most advanced technology available at the time, to ostentatiously enhance the coloration of the girl’s skin. As a result, the dialectics of Black and White are dissolving. Depicting three colors—black, white, and brown—TBB’s cover can be considered a political statement in favor of diversity and of a country choosing to identify as predominantly mixed-raced. Coloring the girl’s skin brown is also a special nod to the eponymous fairy characters of The Brownies’ Book, which are themselves symbols of the variously colored child-readers of the magazine.

The technical quality of the cover is a testament to the skills of both the unidentified printer and the famous photographer C. M. Battey.8 Especially in light of the fact that the technology was, as Dyer contends, “developed with white people in mind […] so much so that photographing non-white people is typically construed as a problem” (89). Du Bois was full of praise for Battey, who had been head of the photography department at Tuskegee Institute since 1916. Battey excels where “[t]he average white photographer” fails (Du Bois, “Opinion” 249). The latter, Du Bois continues, “does not know how to deal with colored skins and having neither sense of the delicate beauty of tone nor will to learn, […] makes a horrible botch of portraying them” (249).

The girl’s face, arms, and neckline are beautifully and strategically enhanced during mechanical reproduction of the original photograph, which might have already been hand-engraved and colorized according to the fashion at the time. Regardless of such speculations on the original, and despite technical enhancement in the printed version, we can see that Battey carefully crafted the colors and contrasts during the photographic procedure in the studio. I disagree with Taylor, who claims that the girl is artificially colored “by a rich brown tint,” and thus “denaturalized,” because “the technology available cannot capture the girl’s skin colour” (751), giving the photographer more credit instead. By enhancing local contrast yet leaving otherwise intact the large-scale contrast scheme of the image, Battey lets the human figure at the center appear three-dimensional. “Backlighting,” Dyer explains, also helps to keep a “figure separate from the background,” while giving “a sense of depth to the image” (115).

Such separation pronounces the girl as different from the dark landscape in the background which likely suggests the American wilderness, or the so-called dark continent (Africa) in front of and against which she is set. As the darkness behind her fails to envelop the girl and render her bare skin indistinguishable, the racist stereotype that devalues African American people as “naturally wild” and “beastlike” by collapsing them with nature is visually challenged. Blackness is neither monochromatic nor monolithic but inherently varied in the picture, thus dislodging the dialectics of Black and White and complicating visual semantics.

Secondly, by shooting with Rembrandt lighting, Battey illuminates one side of the girl’s face while the other remains dark except for a small inverted triangle of light on the cheek. This effective play with light and shadow adds drama to the composition but, more importantly, it makes one side of the girl’s face glow. Such glowing is a photographic effect achieved, at the time, exclusively with White women. As Dyer elaborates, the correct use of light is imperative for the construction of Whiteness in photographs: “Idealised white women are bathed in and permeated by light. It streams through them and falls onto them from above. In short, they glow.” Portrayed by lesser skilled photographers, Black skin tends to shine instead of glow due to “light bouncing back off the surface of the skin” (122).

Battey expertly handles both the “overall and figure lighting” (125) so that the human figure and the background are distinguishable while the girl’s face and arms become the focus of the photograph. Battey redefines beauty standards by reconciliating light and shade in a way that is effective on Black skin only. Instead of exaggerating transparency to the detriment of substance, as is often the case in photographs of White women, Battey manages to administer glow both to the girl’s body and her clothing, the white dress, cape, shoes, and tights—the props of her angel impersonation. Highlighting the Black body and the angel accoutrements, so that Black equals White, is a photographic balancing act playfully matched by the girl’s skillful stance on the tips of her toes.

Furthermore, Battey photographs the girl from slightly below so that the forward-bending reach of her arms and hands comes out even stronger, giving it more of a thrust toward the viewer. The angle from which she is seen provides agency to the girl whose action already speaks of ambition. Contrary to a professional ballerina who, being “all legs” has also been constructed as an object of desire by Romantic ballet which “produced both the most ethereal stage aesthetic and the sex show” (Dyer 131), the prepubescent girl on the cover of the children’s magazine has her upper body, head, and hands, spotlighted. Her feisty hand gesture can be read as signaling defiance—against racist slurs as well as voyeuristic appropriation. This potentially threatening message is again mellowed by her young age while also empowering all children—but especially Black girls—precisely because of the girl’s young age and improvable ballet technique.

The message of the child-angel on the cover of TBB’s inaugural issue is loud and clear. The little imperfections of the young ballerina encourage other children to be ambitious and hardworking in order to excel at what they choose to be doing. This way, they will make an impact like Du Bois or Battey did in their respective fields, thanks to whose sophistication and technical finesse TBB turned out as “a cultural and technological marvel” (Young 12). Read as signifying upon the ballerina’s performance of ideal Whiteness, the hand gesture also expresses TBB’s claim on all the good things White America denies to African American children. With style, technique, and composition carefully attended to, Battey’s image of the African American girl formally signals this “individual’s place in society,” which, Brian Wallis argues, is the key function of the photographic portrait (178). Her stance and defiant gesture add some antiracist spice to the magazine’s nonconfrontational agenda of uplift, thus making the girl a model for “the next generation of freedom fighters” (Alexander 11).

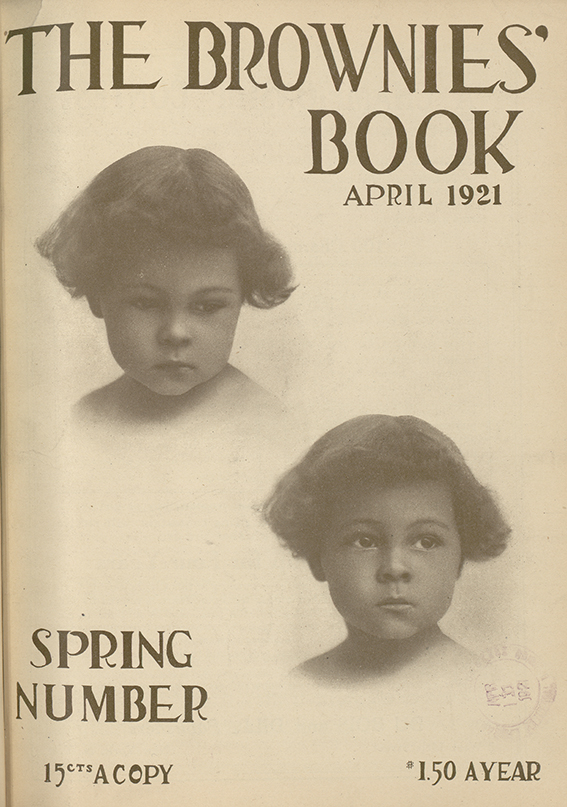

Black Cherubs, Blank Page

TBB’s April 1921 cover again depicted a Black child as an angel (Figure 2). More precisely, it showed two slightly different headshots of what could be the same child or identical twins. The kid on the cover is Yvette Keelan, “granddaughter of lecturer and activist Mary Burnett Talbert,” who “hosted the first meeting of the Niagara movement, forerunner of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, in her Buffalo, New York, home in 1905” (Gates and Tatar 277). The page layout established a narrative that pertained to the child’s family heritage of racial activism, thus indicating the emergence of a new generation of race leaders.

Figure 2. Cover page of The Brownies’ Book April 1921, Online Image. Library of Congress, From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Downloaded March 18, 2021. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=rbc3&fileName=rbc0001_2004ser01351page.db&recNum=512.

The close-ups of Yvette’s head, extracted from the original photographs and free-form selected onto the page, are placed one below and more to the right from the other so that the child appears to be looking down onto her doubled self. Read from left to right, the visual narrative is literally one of uplift as her demeanor changes from sullen, with head bent and eyes downcast in the upper left image, to hopeful in the picture below. Here she holds her head up high, looking into the far and away with eyes wide open and brows raised expectantly. Given Yvette’s light complexion and texture of her wavy hair, this short image-text sequence can also be understood as commentary on the “tragic mulatta,” a stock character of the nineteenth-century American literature where the mixed-race character is portrayed as notoriously unhappy and bound to commit suicide because neither community fully accepts her as their own. She is, in short, an “emblem of victimization” (Raimon 7). Thanks to TBB’s choice in layout, photographic imagery, typography, and coloration, which formally facilitate the message of liberation and amalgamation, the light-skinned child on the cover seems to look into a brighter future than the fictional cliché was ever granted.

Compared with the ballerina depicted on the cover of the inaugural issue, the child of the April 1921 issue sports significant differences. Yvette is considerably younger and, befitting a specific category of angel, she can neither be readily recognized as a girl nor African American. Unlike Battey’s carefully staged studio photograph, the original portraits from which Yvette’s cut-out head has been salvaged could just as well be snapshots adhering to a photographic convention employed with younger children and babies:

Over the course of the nineteenth century, photographic depictions of children shifted from emphasizing their importance as familial heirs to picturing them as individual objects of sentiment, while other popular cultural renderings made ideal children into becurled and dimpled cherubs. (Pearson 345)

Joad Raymond explains the biblical meaning of cherubim as “worldly angels who guard the gates of Eden (Genesis 3:24)” (265). They are of higher rank, yet, in principle, resemble other angel figures, all of which, Amira El-Zein contends, “are good, beautiful, universal, and eternally obedient to God. There is no paradox, no contradiction in their nature” (x-xi). “Simply put,” they are “‘divine messengers’ and beings of light” whose purpose it is to bring “peace and quietude” (xi). Raymond lists their characteristics in more detail: angels “praise God”; they are “messengers and ambassadors” as well as “‘ministering spirits,’ working God’s business on Earth” (85). Furthermore, they are “witnesses” (86). Finally, “angels heal” (86), but they can also be “harbingers of the apocalypse” (90).

In the context of TBB’s modernist aesthetics, which are effects of graphic design, the cherubs’ message on the cover is considerably less sentimentalist and simple. As a result, the “magazine gets to have it both ways, including,” Taylor reasons, “the black child within the sentimental register while also suggesting the perversity of this category” (758). The cherubs, who are “naturally, rhetorical beings, and choose their styles, tropes, and figures to suit the occasion” (Raymond 275), are afforded with the additional function of reflecting on the magazine as a modern medium.

In contrast to the angel ballerina whose rendering deconstructs Whiteness as performance, the cherubs “retain the figure’s fundamental mystique” (Gilbert 253). They are recast in keeping with their traditional iconography as “disembodied spirits,” “luminous beings” and “shape-shifters” (El-Zein 47-48). The difference in representation is significant because the cherubs assume meaning mainly as harbingers of change. Espousing an anticipatory temporality, the cherubs announce a new age, a message that also affects the messenger. To put it in the words of Michel Serres: “Messengers disappear in relation to their message: this is our key to understanding their death agonies, their death and their disaggregation” (80). TBB’s cover mediates the angels’ disaggregation (and along with it their nineteenth-century sentimentalist message) and reemergence as modern media, or even information technology, where Serres believes them omnipresent.

Let me elaborate on how the double effect of disaggregation and reemergence is formally mediated on the April 1921 cover, playing out both in political and medial terms. The soft lower edges of Yvette’s double portrait effect a feathery frizzled look that lets the child’s shoulders merge with the light background of the page. From the blankness that surrounds them, it seems as if the heads of two almost indistinguishable child-angels emerge from the ether. Surfacing only up to their necks and with the physical substance of their lower bodies rendered invisible or absent, they seem suspended in the air, possibly kept airborne by a pair of wings. The pretty, baby-faced heads seem to belong to incorporeal, heavenly creatures. Rendered sexless and looking almost identical, each cherub equally and interchangeably signifies innocence which “foil to adults’ knowingness,” according to the symbolism “derived from representations of putti in art and of the Christ-child in literature” (Wood 117). Their light complexion makes them racially indeterminable, adding another factor to their symbolic condition as pristine and innocent.

Like other angelic children, the cherubs function to exert “redemptive force upon the adults,” Black and White, who just by looking at them let drop—such was the hope—all bad intention and action as they are loved and shamed “into good behaviour” (Wood 119). Taylor states that “the innocent, vulnerable, sentimental child” has its “own particular political value” as “a counter to the racist image of the pickaninny” (739). Given Du Bois’s programmatic indictment of what Naomi Wood calls “a culture that may idealize ‘the Child,’ but fails to protect children who fall short” by not being White (121), TBB’s African American cherubs are visual means of antiracist persuasion. As Du Bois “maintained his faith that American racism could be persuaded and educated away” (Kendi, Stamped 276-77), the reasoning implicit to the cover would go like this: In the face, literally, of such sweet African American children, the racist White, or self-hating Black reader, realizes the absurdity of racial prejudice and is persuaded into giving it up and letting it vanish into the ether. Absorbed and dissolved by the emptiness that surrounds the cherubs, the cover image visually mobilizes blank space as a medium, a “conduit to salvation” (119).

The medial function adds to the obvious meaning of the blank space on TBB’s cover which, like the cherub figure itself, is imbued with racial semantics. Surrounding the cherubs on the material page like a white frame, the blank space symbolizes the racist environment in which African American children live. Du Bois for whom “all art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists” (“Criteria” 296), would not have a commissioned artist employ blanks solely for their stylistic effect. Given that by 1921 the page blanche was not only a standard inventory of modernist poetics but a particularly malleable “cipher open to a variety of procedures and semantics” (Schneider 22-23; my translation), artists of the Harlem Renaissance make blank space work to both political and aesthetic ends.9 For TBB’s cover, they do so in doubly complex ways—as index, the blank space around the cherubs signifies not only oppression by but also liberation from racism. As a medium, it facilitates both the angel’s disappearance and modern media’s emergence.

Adopting the sentimentalized Victorian iconography of the child angel, the nineteenth-century association of the page blanche with transcendental Whiteness is willy-nilly referenced, too. However, as the color white cannot signify an unadulterated state of innocence in the political context of Jim Crow and from an African American perspective, a warm sepia tone is chosen for the blank space on TBB’s cover. Another change in color-coding is made for the typeface. Instead of black, brown lettering is used for the heading, price, and volume information that frame the blank space and portrait composition on the top and bottom of the page. TBB uses “colored tints, particularly on the front covers, and almost always for the sole purpose of representing skin colour” (Taylor 751).

Both sides to the left and right remain, however, unframed by lettering, so that the blank space in the mid-section reaches all the way to the edges of the material page that forms the cover’s outer frame. Given the use of angel symbolism, it is not too far-fetched to assume that the design references a spiritual order with the inner framing on the top and bottom signifying the sanctity of heaven and earth, whereas the open space in-between signifies possibilities. It also warrants change of the social and political condition of African Americans, of a dysfunctional system. This claim is further sustained by the placing of the photographs that mobilizes a narrative image-text sequence. Its dynamism expresses the vitality of “new race leaders,” a vital force to be reckoned with and ideally represented by a very young child cherub.

TBB’s April 1921 cover page is only a detail, yet one that encapsulates the modernist poetics of what Du Bois dubbed “Negro Art” (“Criteria” 290). Unlike other modernist poetics, it does not “highlight the signifier to the detriment of the signified” (Schneider 199; my translation). The cover page is both an aesthetic object and a piece of political propaganda. Its design adheres to a spiritual order in the way that it frames the top and bottom of the page. In leaving the blank space in the mid-section unframed, however, it breaks with traditions in typically modernist fashion. The form of the cut-out photographic images is roundish, and the photos are freely arranged on the page but in an order whose dynamic effect is true to modernism’s desire for the new. In terms of both form and content, the cover page is expressive of modernism’s “esprit nouveau,” a new spirit open to medial enhancements of life and the (social) body (Schneider 140). TBB envisions African American children embracing this new spirit as they grow up with self-respect and trained in skills. Uplifted and liberated from the social and emotional constraints of racism, they gain visibility as a new generation of “race leaders” (Smith, “Childhood” 804).

The doubling of the cherub on the cover—a synecdoche for all children addressed by TBB—is also significant as it indicates multiplicity. The idea extends to TBB’s portrait gallery “Our Little Friends” which showcases “anonymous portraits” (Schäffer 165) of well-groomed, middle-class babies and children. Like their counterparts in Crisis, they are chosen out of hundreds of submissions to offer tangible evidence of the Black middle class. With little or no accompanying text, “Our Little Friends” aims not toward particularity but produces a sense of seriality. Like various other scholars before her, Taylor argues that Du Bois’s preferred practice of presenting the formal studio portraits in “grid-like arrangements over several whole pages” puts them into close and problematic proximity to typological photographs (738).

The children’s portraits are at once generic and specific, self-evident and opaque, signifying simultaneously a racialized type of child (Black) and Du Bois’s “immortal child” of no specific color. Harking back to the sentimentalism of family photography, TBB’s gallery employs the photographs primarily as portraits not of the nuclear family but of extended kinship. They function to visually affiliate all readers, an “imagined community” of extended kin (Anderson qtd. in Taylor 762) to the New Negro Movement.

While Taylor concludes that “[i]n essence, the photographs become decorative almost as a pattern, or a sort of wallpaper” (762), I wish to point out their resistive function. “Our Little Friends” emulates the abundantly pictured photo walls in Southern Black homes described by bell hooks. Covered in “stylized photographs taken by professional photographers” (59), these photo walls “were sites of resistance. They constituted private, Black-owned and -operated gallery space where images could be displayed, shown to friends and strangers” (59). hooks reminisces:

To enter black homes in my childhood was to enter a world that valued the visual, that asserted our collective will to participate in a noninstitutionalized curatorial process. For black folks constructing our identities within the culture of apartheid, these walls were essential to the process of decolonization. In opposition to colonizing socialization, internalized racism, these walls announced our visual complexity. (61)

Like The Crisis, TBB provides a public forum for this private practice, affiliating in the process all African Americans with the child-angel on the cover who extends her angelic qualities to them. In return, the angel is made obsolete. While the angel’s symbolic innocence is employed to prove African American children’s humanity and equal rights, the cherubs, “noncompounded beings” to begin with (El-Zein 48), paradoxically announce their disaggregation. Once humanity, flaws and all, is finally credited to everyone without exception, the angel’s mediated message has been received. The cherubs can now make room for new media like TBB created by and modeled to the demands of the New Negro.

Angel Down

Fitting the season of the year, TBB’s “Spring Number” of April 1921 employed blankness as the discursive figuration of a new beginning. Or, such was the hope. Until today, and as long as racist policy10 continues to make countless African American families mourn the death of their children, the angel despairing to transmit the message of equality cannot disappear. The private photo wall has moved from magazines such as The Crisis and TBB to social media platforms where Black Lives Matter murals keep visual count of the dead and brutalized. Like the angelic child of nineteenth-century sentimental culture, the African American child-angel has become iconographic inventory by now. As an emblem of the innocent victim and Black by default, it pervades popular culture, the medial outlet of both commodified hope and despair as well as Black Lives Matter’s strident call to stop anti-Black police brutality in the United States. This call is echoed by countless activists, including White allies such as Lady Gaga. Ruminating on the death of Trayvon Martin, a teenage victim of anti-Black gun violence, her 2016 song “Angel Down” deploys the African American child-angel, too, begging: “Save that angel, hear that angel, catch my angel” (Lady Gaga).

Notes

[1] “It will be a thing of Joy and Beauty” is a line from the October 1919 issue of The Crisis, the magazine’s so-called “Children’s Number,” in which W. E. B. Du Bois outlines his ideas for The Brownies’ Book (“The True Brownies” 286).

[2] According to Katherine Capshaw Smith, TBB “appeared at the tail-end of one of the most productive moments for black periodicals” (“Roots”). She is certain there were other periodicals for African American children preceding TBB, which is, however, the only one of which copies could have been located.

[3] In December 1913, Fenton Johnson’s poem “Children of the Sun” about Black Christian slaves appeared in Crisis (91). Possibly the editor Du Bois appropriated the phrase “Children of the Sun” to apply to the readers of his children’s magazine. Fenton might have taken earlier inspiration from Du Bois, though. The poem “Easter-Emancipation 1863-1913” (285-88) had already appeared in Crisis in 1913, and, here, Du Bois refers to enslaved Africans as “Children of the Moon” (285). Du Bois includes the poem, now entitled “Children of the Moon,” in Darkwater: Voices from within the Veil. The publication in 1920 coincides with TBB’s, forming a marked contrast to the uplifted and liberated “Children of the Sun.”

[4] Ibram X. Kendi’s acclaimed study Stamped from the Beginning (2016) is a case in point. Kendi’s account of Du Bois’s development from assimilationist to antiracist is compelling. The dialectics of his argument, however, betray a derogative sense of the young, as Kendi pitches youth against maturity, folly against wisdom. His tone gets sarcastic, too, when he somewhat dismissively refers to young W. E. B. Du Bois as “Willie Du Bois,” whom he criticizes for “fiercely compet[ing] with his White peers in the game of uplift suasion, in an attempt to prove ‘to the world that Negroes were just like other people’” (264).

[5] This essay expands on my presentation “Photographs and Family in The Brownies’ Book (1920-1921)” held at the 2017 meeting of The European Study Group of Nineteenth-Century American Literature at the University of Eastern Finland. I wish to thank Sirpa Salenius for bringing The Brownies’ Book to my attention as well as for her and the study group members’ invaluable input on my work. I also want to thank Andrea Frank Adler for engaging in a stimulating dialogue on photography and everything else that matters. Many thanks to Anne Galperin for her expert counsel on the printing process used for TBB’s cover.

[6] Daylanne English criticizes Du Bois’s eugenic photo galleries of NAACP prize babies in The Crisis: “From about 1900 to 1930,” she argues, “uplift took on a more disturbing quality as the period’s notions of racial improvement (for both white and black people) became ever more tightly entwined with the emerging science of genetics” (36).

[7] In Racial Innocence, Robin Bernstein sets out how Black children were denied the status of children in the nineteenth century with a focus on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Epitomizing innocence, the angelic child, Eva, is contrasted with Topsy, the stereotypical pickaninny, who is too dehumanized and amoral to be recognizable as a child. As Eva becomes the cipher for innocence beyond the slaveholding South and far into the twentieth century, the child becomes White by default.

[8] Battey’s excellence was representative of many other Black photographers. The legacy of African American photographers, thoroughly documented and researched by Deborah Willis, begins in 1840 when “Jules Lion (1810-1866), first introduced the daguerreotype process to the city of New Orleans” (Introduction xv). In his lead and despite “pervasive racial discrimination,” Willis states, “hundreds of free men and women of color established themselves as professional artists and daguerreotypists during the first twenty-five years of photography’s existence” and “began to record the essence of their communities mainly through portraiture” (xvi). Portrait photography quickly became a tool “to resist misrepresentation,” and the camera persistently sustains the political struggle for racial equality, bell hooks writes in “In Our Glory” (60).

[9] The blank space on the cover of TBB is characteristic of the U.S.-American cultural and political context. Yet, the implications of race and gender for cultural practices and discourses are far less insignificant and more generally pervasive than Lars Schneider’s study suggests. To analyze the work of seven White male Modernists who are all but one (Herman Melville) based in France (a former colonial power) without even so much as a nod to race and gender politics constitutes itself a blank.

[10] “Racist policy,” defined by Kendi as “any measure that produces or sustains racial inequity between racial groups” (Antiracist 18), plays out in terms of racist terror, concomitant a lack of accountability for those responsible due to a “legal system [that] condones those killings” (Crusto 7), and crass economic disparity.

Works Cited

Crusto, Mitchell F. “Black Lives Matter: Banning Police Lynchings.” Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly 48.1 (2020): 1-72. SSRN. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3747340.

Du Bois, W. E. B. “Criteria of Negro Art.” The Crisis 32 (1926): 290-97. WEBDuBois.org. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. http://www.webdubois.org/dbCriteriaNArt.html.

---. “Easter-Emancipation, 1863-1913.” The Crisis 5.6 (1913): 285-88. Modernist Journals Project. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr520221.

---. “Opinion of W. E. B. Du Bois.” The Crisis 26.6 (1923): 247-50. Internet Archive. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. https://archive.org/details/crisis2526dubo/page/242/mode/2up?q=opinion+.

---. “The True Brownies.” The Crisis 18.6 (1919): 285-86. Modernist Journals Project. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr512545/.

Du Bois, W. E. B., and Jessie Redmon Fauset, eds. The Brownies’ Book. New York: Du Bois and Dill, 1920-1921. Library of Congress. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.rbc/ser.01351.

Fern, Kory. “Once upon a Time in Aframerica: The ‘Peculiar’ Significance of Fairies in the Brownies’ Book.” Children’s Literature 29 (2001): 91-112. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1353/chl.0.0803.

Gilbert, Roger. “Awash with Angels: The Religious Turn in Nineties Poetry.” Contemporary Literature 42.2 (2001): 238-69. JSTOR. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1209122.

Johnson, Fenton. “Children of the Sun.” The Crisis 7.2 (1913): 91. Modernist Journals Project. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr517675.

Lazarus, Emma. “The New Colossus.” 1883. Liberty State Park, n. d. Web. 19 May 2021. http://www.libertystatepark.com/emma.htm.

Oeur, Freeden Blume. “Children of the Sun: Celebrating the 100-Year Anniversary of The Brownies’ Book.” Children & Youth. American Sociological Association, 29 May 2020. Web. 31 May 2021. https://childrenandyouth.weebly.com/blog/archives/05-2020.

Pearson, Susan J. “‘Infantile Specimens’: Showing Babies in Nineteenth-Century America.” Journal of Social History 42.2 (2008): 341-70. JSTOR. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27696444.

Phillips, Michelle H. “The Children of Double Consciousness: From The Souls of Black Folk to The Brownies’ Book.” PMLA: Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 128.3 (2013): 590-607. JSTOR. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23489295.

Smith, Katherine Capshaw. “The Brownies’ Book and the Roots of African American Children’s Literature.” The Tar Baby and the Tomahawk: Race and Ethnic Images in American Children’s Literature, 1880-1939. U of Nebraska-Lincoln and Washington U in St. Louis, 2016. Web. 19 May 2021. http://childlit.unl.edu/topics/edi.harlem.html.

---. “Childhood, the Body, and Race Performance: Early 20th-Century Etiquette Books for Black Children.” African American Review 40.4 (2006): 795-811. JSTOR. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40033754.

Taylor, Julie. “Mechanical Reproduction: The Photograph and the Child in The Crisis and The Brownies’ Book.” Journal of American Studies 54.4 (2020): 737-74. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875819000045.

Williams-Sanchez, Valerie L. “The Brownies’ Book.” The Reading Professor 24.1 (2019): 1-29. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. https://scholar.stjohns.edu/thereadingprofessor/vol42/iss1/5.

Young, Patricia A. “The Brownies’ Book (1920-1921): Exploring the Past to Elucidate the Future of Instructional Design.” Journal of Language, Identity, and Education 8.1 (2009): 1-20. Web. 28 Feb. 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15348450802619946.