- Jahrgang 65 (2020), Ausgabe 2

- Vol. 65 (2020), Nr. 2

- >

- Seiten 213 - 233

- pp. 213 - 233

- Zurück

“Pruitt-Igoe in the Suburbs”: Connecting White Flight, Sprawl, and Climate Change in Metropolitan America:

Abstract

This article explores the connections between racial inequality and fossil fuel-intensive sprawl in the post-civil rights metropolitan landscape, through a case study of the Black Jack housing controversy. In 1970, a local religious group tried to build a low-income housing project in Black Jack, Missouri, a bedroom community four miles northwest of the city of St. Louis. Local residents opposed to the project argued that public housing would bring the crime, poverty, and social disorder of the city to the suburbs. Although they were forced to strip their opposition of overtly racist language, these White suburbanites were part of a nationwide project to racialize, and thus delegitimize, the extension of urban form into American suburbs, including public housing and public transportation. When these efforts failed, as they did in Black Jack, inner-ring suburbs began to desegregate, and in response, Whites again fled, further out, to second-ring suburbs and exurbs. This process, which has played out across American cities from the 1960s until the present day, has had devastating consequences for racial and economic inequality, but also on the global climate. Millions of White Americans, driven by their desire to maintain metropolitan racial segregation, have become hostile to the forms of urban infrastructure that would create less carbon-intensive cities, recreating racist, auto-intensive sprawl farther out into the countryside.

The drive from the north side of the city of St. Louis to O’Fallon, a far-out exurb, helps explain a lot about American cities. Once a vibrant community of red-brick rowhouses that made this river city a powerhouse of American industrialization in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, today the north side has much in common with some of the most depopulated parts of Detroit, the South Side of Chicago, and other Rust Belt cities. Entire blocks sit empty, or with just one or two houses still standing. Census tracts that once held as many as 30,000 people now have less than 5,000, with the number declining every day. Thirty miles west is O’Fallon. Right off I-70, twenty-five years ago O’Fallon was a rural community with fewer than 20,000 residents. Today it has almost 100,000, with the vast majority living in single-family homes, and shopping at malls and plazas with the predictable big-box stores.

This essay explores the connections between the continued evolution of metropolitan inequality in America and the development of energy-intensive sprawl, by looking at a place in the middle, between St. Louis and O’Fallon: Black Jack, Missouri. In 1970, a local religious organization tried to build a subsidized housing complex, named Park View Heights, in Black Jack. In response, the residents of Black Jack, which heretofore had been unincorporated, formed their own municipality, and then zoned the planned complex out of existence. The sponsors of the project, working with the American Civil Liberties Union, sued the new city, arguing that the zoning regulation violated federal civil rights law. A U.S. appellate court agreed, striking down the ordinance, and setting an important new precedent for housing rights. This was only the beginning of a decade-long legal battle, however, and ultimately the project was never built.

All along the I-70 corridor, from St. Louis to Black Jack and then all the way out to O’Fallon, one can see the results of more than half a century of local, state, and federal urban development policies, and the racialized real estate markets they helped create and reinforce, which privileged the suburbs over the central city, draining resources and capital. The result has been slow-motion metropolitan decay and decentralization, with its attendant destruction of many primarily minority central city neighborhoods. O’Fallon and the rest of the surrounding St. Charles County has also reliably been one of the most politically conservative counties in the nation, actively supporting electoral candidates and policies that have undercut the economic safety net and enforcing the types of punitive policing that only exacerbate, not solve, the social problems that the communities of north St. Louis face. This story of “suburban secessionism,” where White residents actively flee central cities and construct their lives in opposition to the city, with no acknowledgement of the role their politics and attitudes play in constructing and reinforcing inequality, is one that urban and political historians have become adept at telling (Kruse 234).

But there is another story along this drive, because the only way to get from central St. Louis to O’Fallon is to drive, and, in the process, expel an average of about forty pounds of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere on each round trip. Metropolitan St. Louis, especially along the I-70 corridor, is a sprawling, low-density conurbation that epitomizes what Chris Wells has called “car country,” a landscape designed in a specific way to privilege, and thus become dependent on, the automobile. It is primarily made up of single-family homes, with the occasional low-rise apartment complex. Some of the residents of O’Fallon and surrounding suburbs work in St. Charles County, but many commute eastward every day, into St. Louis proper, or to jobs in the hospitals, office parks, and low-rise factories that surround the city in suburban St. Louis County. This has made O’Fallon and the surrounding communities some of the biggest contributors to global climate change in the region. Each household dumps an average of seventy metric tons of carbon into the atmosphere every year, the majority through gasoline to power automobiles and coal to heat and cool their single-family homes. Contrast this with communities in central St. Louis, where the household carbon load is less than half that, about thirty tons per year or less. According to the CoolClimate Project at the University of California, which mapped household carbon use by income across the United States, this urban/suburban split is the standard for almost every major American metropolis. Central cities average twenty-five to thirty tons of carbon per household per year, while suburbs are usually twice that or more (Jones and Kammen).1

These stories, one of racial and socioeconomic inequality, the other of fossil-fuel dependence, climate destruction, and unsustainability, are two of the biggest challenges that American cities face in the twenty-first century. But these are stories we rarely tell at the same time, despite the fact that they are intimately intertwined.

The Black Jack case was one of a spate of conflicts that occurred across the country, beginning in the late 1960s, between advocates of equitable housing and the residents of outer urban and suburban neighborhoods. As capital and resources drained from both public and private housing markets in central cities, African Americans continued to push for access to better housing in safer neighborhoods across metropolitan areas, either through open housing laws or new subsidized housing projects (Danielson). Although federal civil rights laws were almost always on their side, especially after 1968, legal victories were often pyrrhic, as residents and local governments fought tooth and nail to keep communities and suburbs all White, delaying projects so long that funding dried up or limiting their scope so that they did not provide any real remedy to larger structural issues (Massey et al.).

The Black Jack case is an important part of this civil rights and fair housing narrative, an early battle in the push to open up the suburbs to African Americans and other minorities. Despite the failure of this particular project, the story in St. Louis was, from one perspective, a victory. The suburbs went from being virtually all White in the late 1960s to having a significant, and growing, African American population by the early 1980s. For example, Black Jack and the surrounding areas had about three hundred Black residents in 1970, but more than five thousand by 1980. But the Black Jack story, and other similar conflicts over open and public housing in the post-civil rights metropolis, are worth re-examining, because they have significant import for understanding our currently distended, inequitable, and unsustainable metropolises. Most significantly, it is important not to collapse the Black Jack case together with earlier incidents of White opposition to housing integration from the 1940s through to the 1960s (Hirsch, “Massive Resistance in the Urban North”). Although the protection of property values (and thus capital investment) and racial identity was still a significant part of White opposition in the 1970s, the landscape had changed. The cultural, social, and most importantly legal successes of the civil rights movement had made overtly racist language, pronouncements, and policies unacceptable in civic life and subject to legal sanction, primarily through the courts. But, at the same time, a new language, set of attitudes, and, ultimately, policy tools became available through the specter of the urban crisis. Suburbanites now saw the urban protest, poverty, and crime of the 1960s as the most important threat to their suburban security (Kohler-Hausmann; Lassiter).

The Black Jack controversy happened right at the center of this shift. Civil rights laws were making overt forms of discrimination illegal, but suburbanites had new and specific images to deploy (in this case, the presumed failure of public housing) to try and defeat attempts at residential integration. But to defeat the city, they also had to defend the suburbs. They could not use overtly racial language, so they defended it as a specific type of spatial form and built environment: single-family homes only accessible via automobile. Higher-density apartments, which might require access to public transportation and/or need to be within walking distance of other services and employment, were not a good fit in these neighborhoods, they argued. In one flyer distributed across the community, opponents argued that the construction of Park View Heights would lead to “substantial worsening of the already grave problems of the Hazelwood School District,” a “traffic congestion nightmare” on local roads, “overcrowding of local churches,” and the creation of additional burden for fire and police departments (Black Jack Improvement Association).

Ultimately, the new town of Black Jack would attempt to use a zoning ordinance to prevent the construction of Park View Heights. But this was not just a land-use issue. Zoning was just one of a cornucopia of tools—lot-size restrictions, open-space provisions, water and sewer construction—that the White residents of Black Jack and other American suburbs would increasingly deploy from the 1970s onward to maintain what James and Nancy Duncan call the “landscapes of privilege” (2). Land-use laws and developmental regulations have been used across the country to entrench and continuously recreate a social hierarchy built around the low-density, car-dependent, single-family home community. Sitting in opposition to this was the built environment and infrastructural system of the city: high-density apartments, publicly subsidized housing, and walkable neighborhoods intricately interwoven with accessible public transit. This conflation and opposition would have devastating consequences for racial equality in America, but also for sustainability and the future of human society. American-style suburbia is arguably the most energy-intensive form of urban development the world has ever seen. And from the late 1960s to today, White suburbanites continue to oppose anything that will make it more energy-efficient and lessen its dependence on fossil fuels, including public housing, apartment complexes, or any form of real density. Although, at first glance, the arguments often involve protecting housing values or neighborhood character, the subtext, and sometimes the text, of their assertions are racial. Suburbanites worry that the apartment or public housing complex will bring Black people to their communities and with them crime, poverty, drugs, and despair.

In Black Jack and the other locales, the first response was to fight back against the new apartment complex and any extension of public transit. But oftentimes that did not work, especially with strong civil rights laws and local activism. So what was the next answer? Move farther out, into new jurisdictions, like St. Charles County and O’Fallon, where most residents owned single-family homes, there was no regional public transit, and to get anywhere you had to drive, sometimes fifteen minutes just for the grocery store, burning seventy tons of carbon into the atmosphere every year. Over the past forty years, St. Charles County has almost tripled in size, from 144,000 residents to about 400,000. The vast majority, ninety percent, of these residents are White, and only about five percent are Black. This is contrasted with sections of northern St. Louis County, which today are seventy to eighty percent African American (United States. Bureau of the Census).

“Solving the problem of race is not only the most urgent piece of public business facing the United States today; it is also the most difficult” (Silberman qtd. in Heckman and Ritvo). This was on the cover of a 1969 brochure from the St. Louis Inter-Religious Center for Urban Affairs, an ecumenical organization formed two years earlier by local Protestant churches, most from affluent suburban congregations, to address social issues. The ICUA engaged in a variety of activities, such as training White congregants about the impact of White privilege, but its biggest activity was in housing. The center set up an Ecumenical Housing Fund, which raised almost $300,000 from local churches to help support a variety of low-income housing projects in the St. Louis metropolitan area. The earliest payments were grants to assist other nonprofits, but at the end of 1969, the group announced that they would develop their own project by directly funding a subsidized housing complex that would have apartments and attached townhomes for rental, with a first phase of 108 units. The ICUA was the primary developer, the sponsor was St. Marks, a local Methodist church, and the project was financed through the federal government under what was known as the “Section 236” program (Calkins). Named after a section in the Housing and Urban Redevelopment Act of 1968, the program provided subsidies to cover mortgage interest payments for the construction or rehabilitation of multifamily housing projects. With less overhead, project developers could charge much less in rent. By cutting mortgage interest rates from, on average, eight percent to one percent, Section 236 was designed to entice private developers, for-profit and nonprofit alike, to provide more lower-cost housing, thus increasing the overall number of affordable units across the country at a faster rate, and a lower cost, than the federal government could accomplish alone (United States. Government Accountability Office). The ICUA’s planned cost for the initial phase of the project, to be named Park View Heights, was about $1.8 million. With the Section 236 subsidy, they were able to save more than $120,000 per year in interest, lowering the average rent of each apartment by about fifty percent. With the subsidy from the Section 236 program confirmed, the ICUA began looking for sites in St. Louis County, eventually finding a twelve-acre tract in Black Jack, an unincorporated community in the northern part of the county. They filed for a construction permit with the county government at the end of 1969, and the project was announced in January 1970 (Heckman and Ritvo).

The ICUA and the Section 236 program emerged at an important inflection point for housing policy in the United States in general, and St. Louis in particular. Over the previous two decades, the country had experienced some amazing housing successes, along with some glaring failures. The success was primarily the suburban housing boom. Fed by postwar prosperity and significant government subsidy, millions of Americans were able to purchase new single-family homes in newly developed communities outside of major cities. The failure was that the market for these homes was thoroughly racialized, making home purchases, and low-interest mortgages specifically, available almost exclusively to Whites. This confined African Americans to particular areas of the city, where landlords had an incentive to raise rents and skimp on maintenance. By the 1960s, with poor African Americans continuing to migrate from the rural South to cities across the country, this brought about a housing crisis that manifested itself in protest movements, both formal and informal (Theoharis and Woodard). Anger over substandard housing conditions and exploitive economic practices sat at the center of both the urban iterations of the Black Freedom Struggle and the wave of urban uprisings and riots that spread throughout American cities over the course of the decade, peaking with the Easter Rebellion in 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. (Levy 153-88). The response by Congress to this unrest and inequality was the 1968 Civil Rights Act, colloquially known as the Fair Housing Act, which outlawed discrimination in most forms of buying, selling, leasing, or renting property. To many civil rights activists, this was the obvious next step in ensuring a just and equitable society.

Although St. Louis did not experience any of the large-scale violence that other cities faced during this period, it had a robust civil rights movement, with activists and organizations putting significant focus on access to decent and affordable housing. Arguably the city’s most important housing rights movement was related not to private but to public housing: the Pruitt-Igoe Rent Strike.

Hailed as a design marvel and boon for St. Louis’s low-income residents when it was constructed in the 1950s, the thirty-three towers of Pruitt-Igoe had reached a financial crisis a decade later. The project had been conceived in the 1940s, when St. Louis was a densely populated city of more than 800,000 people (Heathcott 39). But as the suburbs boomed and the city decentralized, more housing opportunities opened up to working-class St. Louisans, especially Whites, and the buildings were rarely at full capacity. This starved Pruitt-Igoe of maintenance income, which led to a rapid physical deterioration of the entire complex and a spike in vandalism and crime. Residents responded with a vigorous series of protests, and their activism was successful in the short-term, but a continuing lack of demand and long-term maintenance costs quickly overwhelmed the city budget, and Pruitt-Igoe was demolished over the course of the 1970s (Karp).

Pruitt-Igoe is important for a number of aspects of the Park View Heights story, including as an initial motivator for the financing and construction of the project. Publicly subsidized housing has always been heavily suspect in the United States, seen as a threat to private property and individualistic values and as a competitor to the private market. Pruitt-Igoe was part of a wave of large-scale high-rise projects constructed directly by local governments (with federal money) from the late 1940s through the early 1960s. These tower-in-the-garden projects, so-called because they paired high-rises with green space, were not just supposed to provide low-cost housing. They were also intended to fulfill larger social goals of helping the poor and working-class become better people (Hunt). But by the end of the 1960s, a new housing regime began to emerge. Instead of constructing and operating housing directly, local, state, and especially federal agencies would provide housing assistance indirectly, through rental vouchers, tax breaks to private developers, and mortgage subsidies to nonprofits. Section 236, although ostensibly created because the perceived need for housing was so great that it was essential to enlist the private sector, was directly in this vein of indirect social provision (Vale and Freemark 388).

It is within this context that the ICUA conceived of Park View Heights in Black Jack, with the goal of creating quality affordable housing for lower-income St. Louisans and providing access to the suburbs for residents of central St. Louis, primarily African Americans. Housing markets in St. Louis were still rigidly segregated in 1970, making it virtually impossible for most African Americans to purchase or rent any home in a White community, regardless of their income or ability to pay. This was especially true in fast-growing St. Louis County, which was (and is) primarily suburban in character. This had a negative impact on the prospects and life outcomes for Black residents in a number of ways, but the ICUA primarily considered the problem as one of a lack of access to resources. The members of the ICUA and other White, liberal groups in the region argued that because they had few housing options, Black St. Louisans, especially those in the working and lower-middle class, could not get access to safer, lower-crime communities, well-paying jobs, and better schools for their children. The solution was to relocate them to the suburbs, where, ostensibly, all of these amenities were abundant, thus improving their lives and the long-term life outcomes for their children. “It is the feeling of the sponsoring group that this beautifully designed group of homes will provide a much-needed alternative environment to families of moderate income desiring better housing,” stated a memo distributed by the ICUA to Black Jack residents to dispel myths about the project (ICUA, Park View Heights).

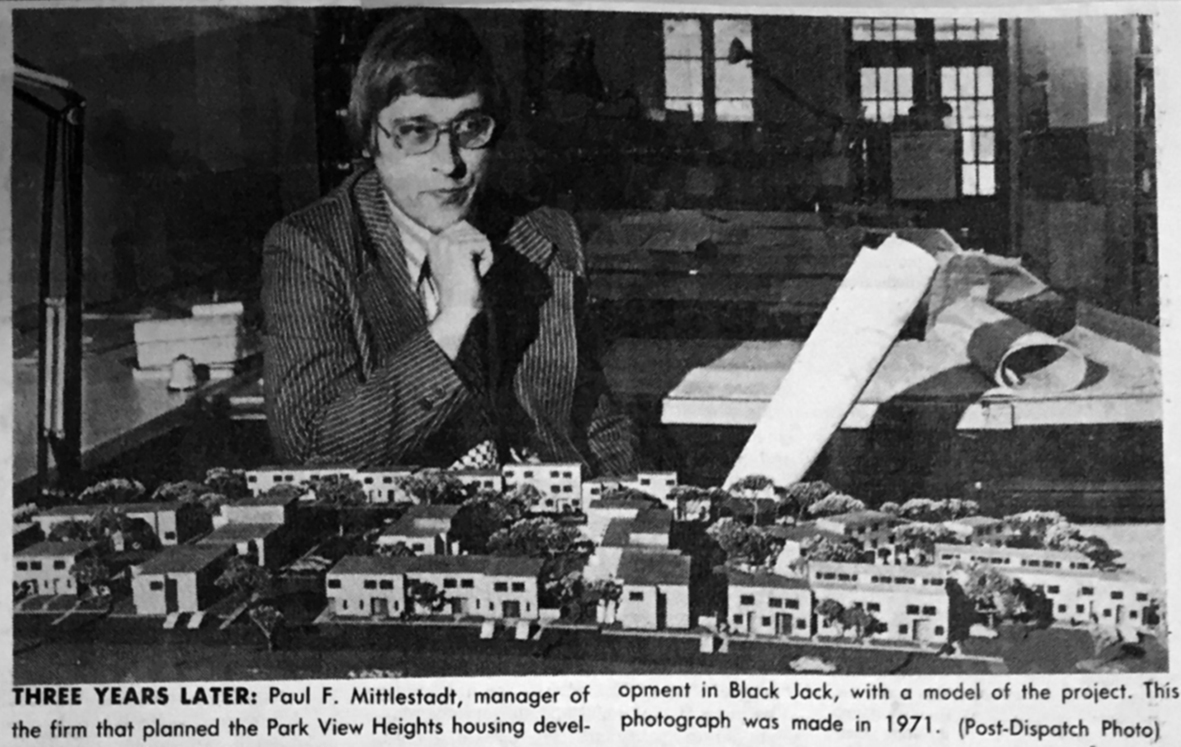

In these and other public statements to defend the Park View Heights project, ICUA staff and leadership were engaging in a form of respectability politics, arguing that the project’s future residents were families with good jobs deserving of this opportunity and not a threat to the residents of Black Jack. In reality, Paul Mittelstadt, the director of the housing program, and Jack Quigley, the director of the ICUA, had initially been reluctant to pursue the project. They saw themselves as predominantly committed to working with Black groups to try and improve housing conditions for the poor in the central city. But some members of the alliance, particularly a liberal faction from St. Mark’s, a large Methodist congregation in Florissant, a few miles west of Black Jack, had convinced them of the need for a suburban project (Heckman and Ritvo). But once the project got underway, the ICUA’s defense of it had the perverse effect of reinforcing the contrast between city and suburb, constructing “the city” as the site of social dysfunction—high crime, failing schools, and lack of quality housing—and the suburbs as the mirror opposite. Open access to housing in the suburbs was not something that should be provided simply as a democratic right, but as a form of social welfare that was the only hope for improving living conditions for Black families.

This contradiction was common among the city’s White open housing activists, and the city’s preeminent open housing organization, the Greater St. Louis Committee for Freedom of Residence (FOR), would often strike a similar tone. Originally organized by a group of White and Black professionals to provide equal housing opportunities around Clayton and University City, in the central part of St. Louis County, FOR generally emphasized open housing as a democratic right, and argued that integrated housing would decrease racial tension and animosity. “As they move into all-white areas and use the schools, churches and public facilities, white neighbors will have a chance to really know [African Americans] as people,” a FOR brochure argued (Freedom of Residence Committee, A New Balance). But in working to emphasize that Black St. Louisans were solid citizens and good neighbors, the committee and other open housing groups often focused on providing purchase or rental opportunities for middle-class families who wanted access to the suburbs (Ritter).

Arguing that there were certain African Americans who were respectable, had good jobs and stable lives, and were thus deserving of a place in the suburbs was a pragmatic political tactic for the FOR Committee and Protestant liberals who pushed for the creation of Park View Heights. This reveals the limits of suburban liberalism, a dynamic also highlighted in Lily Geismer’s study of suburban Boston. As well-meaning as the activism was, it still reinforced, in the minds of White suburbanites like the Black Jack residents, that there were those who were not respectable, whose lives were marked by social disorder, and who lived in public housing, which is one of the reasons why Black Jack’s residents saw the planned development as such a threat. They began to raise opposition to the project almost as soon as it was proposed, writing letters to county officials and lobbying the federal government through their subdivision improvement associations. A delegation even went to Washington, D.C., in April 1970 to speak with officials from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), but they were rebuffed and told that HUD would continue to support the project (“Spanish Lake Residents Set Up Housing Fight”). Mittelstadt, who started out as project director for ICUA but eventually became the lead developer for Park View Heights, had followed all of the necessary regulations at the local, state, and federal levels. Residents then sent threatening letters to the pastor and congregants of St. Marks, the primary sponsor of the project (Heckman and Ritvo; ICUA, Development; Figure 1).

The opponents of Park View Heights did have reason to believe that resistance alone would stop the project. It had worked a couple of years before when “strenuous local opposition” prevented the construction of about 600 units of public housing in three sites on the south side of the county, primarily at Jefferson Barracks, a decommissioned U.S. Army base. According to a local official interviewed by the U.S. Civil Rights Commission about the barracks project, “local opposition to public housing was primarily racial” (United States. Commission on Civil Rights 17). Political pressure from Henry Bischoff, a St. Louis County Council member who was opposed to the project, did force the original developer, the firm of Fischer and Frichtel, to back out, but in general all principles stood firm (ICUA, North County Project). As a coalition of Protestant churches, the ICUA had weight and influence in the community, and the FOR and other groups had created a tempered acceptance for racial liberalism in greater St. Louis that was generally supportive of social service and community development projects that fit within a more moderate, integrationist vision. Opponents of the project sought the support of members of the school board, arguing that their local elementary school was already overcrowded and would be overwhelmed with new students from Park View Heights. Contending that the local school was in crisis was of course ironic, because in other venues Black Jack residents argued that it was the strength of the local schools that had attracted them to the neighborhood. The school argument even provoked a rebuke from the generally conservative editorial page of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, which called this strain of opposition “wholly unacceptable in principle, if not illegal as well” (“Discrimination by Zoning”). With all existing routes of recompense restricted, the residents followed what they believed to be their only option: incorporation. Black Jack would go from being an unincorporated part of St. Louis County to its own independent municipality. This would allow it to set land use and zoning laws, effectively giving it the power to zone the Park View Heights project out of existence.

So far, the opposition by the residents of Black Jack to Park View Heights, an opposition so strong that they went to the expense and trouble of creating a new city, looks familiar to other stories of White hostility to metropolitan housing desegregation in twentieth-century American cities. White suburbanites fought vehemently, oftentimes through violence, to protect the racial privilege of owning a home in an all-White neighborhood. As David Freund and others have shown, this opposition was not just about simple bigotry and racial animosity (although there was always plenty of that), but about maintaining a form of Whiteness that had been built into the landscape, through the single-family home, that brought significant economic benefits (Freund). But the character and tenor of this opposition changed throughout the twentieth century, and we can detect a new form emerging with the Black Jack incorporation case.

One of the striking aspects of the opposition to Park View Heights is the almost real-time effort by Black Jack residents to try and avoid obvious, and then veiled, uses of racial language. At various points in the spring of 1970, Black Jack residents argued that the government was trying to bring “trash people” into the suburbs (“Housing Discrimination Suits”), that people are “more comfortable with those of their own race,” and that any residents of the future housing project should all be “shipped back to where they came from” (Wilson). In internal documents, ICUA staff recounted how all encounters with Black Jack residents were hostile, and Mittelstadt even feared for his safety at mass meetings held to dispel rumors about the project (ICUA, Development). But a few months later, the tenor and language of the opposition changed noticeably. Almost all forms of outright bigotry and hostility disappeared. Residents instead emphasized infrastructural (too much traffic and overcrowded schools), economic (declining home values), and political (self-determination) concerns as reasons why the project should not be built. Because this shift in discourse coincided with the decision to pursue incorporation as the primary strategy to stop the project, evidence from newspaper articles and internal ICUA and court documents shows that residents understood that explicitly racist language was no longer acceptable, either legally or politically (Heckman and Ritvo; United States of America vs the City of Black Jack).

With racial animus no longer socially acceptable, Whites, especially when defending suburban land use prerogatives, attempted to adopt a rights-based, color-blind language that marginalized claims for equality and justice. This sort of rhetorical shift was common throughout metropolitan America in the late 1960s and 1970s. As Matthew Lassiter, Kevin Kruse, and others have argued, color-blind language allowed Whites to maintain a certain racial innocence around their privilege. But the emphasis on “colorblind conservatism” within much of the historiography ignores the fact that race did not disappear from the language of suburban Whites. It was re-sculpted into a powerful new discourse built around the threat not of People of Color directly, but of the urban institutions that many of them used or depended upon for daily survival, especially public transit and housing.

This is why the invocation of the threat of public housing by Park View Heights opponents, and their fear of “another Pruitt-Igoe” specifically, is so important. Pruitt-Igoe failed because of a complex interaction of deficiencies in both local and national policy, from the 1940s to when the buildings were finally imploded in the 1970s. But to White St. Louis suburbanites, it failed because it was a publicly subsidized housing complex. Mittelstadt, the ICUA, and other groups involved in the development of Park View Heights knew this and went to great lengths to argue that although their project was subsidized by a federal program, it bore little resemblance to Pruitt-Igoe. In newspaper articles, public statements, and documents disseminated to Black Jack residents, they argued that Section 236 subsidized mortgage costs so that initial rents would be lower, but that all residents would be expected to pay rent. This was not housing for the poor, but for “families of moderate income desiring better housing.” Because the project was overseen by a group of churches, it would arguably have better, more conscientious management than a for-profit apartment complex, they argued. “The Park View Heights Corporation will especially seek out upward-mobile young families for tenancy—such as teachers, nurses, plant workers and graduate students,” according to a mailing from the sponsoring organizations to all area residents in June 1970 (ICUA, For Your Information). Park View Heights’ developers were working assiduously to distance themselves from Pruitt-Igoe and other high-rise housing complexes. “One of the strange ideas going around is that we’re going to have welfare families living there. They couldn’t possibly afford it,” Mittelstadt argued in one newspaper interview about the need for the information campaign (Donhowe 4). But in the process, they were also reinforcing the metropolitan boundaries that the apartment complex was ostensibly trying to break down. The suburbs were a place for “upward mobile” families who had, or aspired to have, middle-class incomes, implying that the city was the site of disorder in the metropolis and the home of African American poor and working-class people.

The majority of Black Jack residents, however, would not accept any of these assertions. From the summer of 1970 forward, they argued that they were opposed to a publicly subsidized apartment complex in a suburb of single-family, residential homes. Their contentions, outwardly stripped of racial language, worked to emphasize class. “If they want to come out here and pay their money like the rest of us, then that’s all right,” resident John Sexauer told a St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter in 1971. “Nobody helped me. I’ve had to earn every dime I got by myself and I feel they should do the same way” (Defty 1). Robert Schuchardt, chair of the young city’s zoning commission, echoed Sexauer. “The only criterion for entering Black Jack has been the ability to pay. For your information, we are not a racist community. But neither are we for economic integration,” he said in another article discussing the zoning ordinance (Zoeckler). Schuhardt’s and Sexauer’s statements were not just front-porch commentary to inquisitive reporters, but part of the city’s official response to the federal court ruling that declared their zoning ordinance violated national civil rights laws. In the almost hundred-page document defending the ordinance that outlawed multifamily dwellings, lawyers made copious assertions that Black Jack was an “upper income community” where the construction of multifamily dwellings did not fit the “character of the community,” arguing that apartments lowered property values and would overwhelm infrastructure. They also argued that Park View Heights, and most apartment or multifamily home complexes, were ill-suited to the suburbs because of the lack of public transportation. It was assumed that residents of the new community would not own cars, and that they would need access to the public bus system, which did not serve the suburban community at that time (Wilson).

In addition to making these many positive arguments about the benefits of their community and the threat that a publicly subsidized, multifamily dwelling presented, the residents and officials of Black Jack also had to defensively assert that they were not motivated by racial animus. This was partially a legal strategy. One flyer from the Black Jack Improvement Association, which initially fought Park View Heights and then led the incorporation drive, instructed residents to “[p]lease avoid emotionalism, threats or bias against minority groups which could only serve to hurt our cause” (Black Jack Improvement Association). Proponents of incorporation and the new zoning law knew that their statements and actions would be held up to scrutiny if a lawsuit was filed and they were accused of violating civil rights laws. Their primary evidence that their opposition was not racially motivated was that the community did contain almost thirty Black families, and two members of the newly created zoning board that passed the law outlawing multifamily dwellings were African American. Their presence was mentioned in detail in every argument, newspaper article, and legal document as proof that the city was not motivated by racism because it was already integrated. When those Black residents were actually surveyed as to what they thought about the controversy, their feelings were mixed. Oscar Williams was a young engineer at the nearby McDonnell-Douglas plant. He did not support incorporation because he felt it was racially motivated. Nevertheless, he was opposed to Park View Heights, primarily because he knew that the new residents would not be welcomed in the community. “People moving in here would get the feeling they are not wanted. It will make them feel alienated and prevent them from becoming part of the community,” Williams said (Zoeckler).

Despite the claims of White Black Jack residents that their motivations were free of racial animus, it is impossible to disaggregate race and a fear of the city from their opposition to the Park View Heights project. Lurking beneath, or oftentimes right alongside, class-based, color-blind assertions was a new language that spatialized race and collapsed it together with supposedly dysfunctional urban institutions. In the same article in which the newly elected mayor Keith Barbero calls Black Jack “one of the most beautifully racially integrated communities in the country,” an unnamed resident also says that “[i]t’s not race we are talking about per se, it’s the degradation of the neighborhood; being able to walk the streets at night, safely. It’s fighting against the establishment of another Pruitt-Igoe in the suburbs” (Zoeckler). This assertion about Pruitt-Igoe was actually the most common refrain of opposition to the project. Public and private comments from Black Jack residents and officials are riddled with mentions of the public housing complex. “When I look at those slides, that is Pruitt-Igoe,” said a Black Jack resident at a public meeting where Mittelstadt showed images of Park View Heights to emphasize how it was not a high-rise complex (McGuire). At another community meeting, a resident complained that the community was being targeted because “the North County has been singled out to dump Pruitt-Igoe type relief workers” (“Political Figures Voice Opposition to Housing Proposal”). This use of the phrase Pruitt-Igoe was so common, in fact, that the U.S. District Attorney’s office, in its primary brief to the court claiming that the Black Jack zoning law violated civil rights law, created a separate section where they argued that “Pruitt-Igoe” was the most prominent racial euphemism used by Park View Heights opponents. Because there was actually very little physical similarity between the projects, the brief argued, “‘Pruitt-Igoe’ is an emotional term which agitates rather than describes.” Two HUD officials from St. Louis testified “that Pruitt-Igoe means Black as well as poor, crime and failure, and several other witnesses held the same view” (United States of America vs the City of Black Jack 35).

From the perspective of the federal civil rights lawyers, Pruitt-Igoe was a euphemism for race, a key piece of evidence to prove that the patently racist intent of the actions of Black Jack officials and residents violated civil rights law. But it is important not to write off the invocations of Pruitt-Igoe as simply a new form of racially coded language or dog-whistle politics. The way Park View Heights talked about Pruitt-Igoe mattered, in that it lays bare the new spatialized form that racism was taking in metropolitan America in the late 1960s and 1970s. As another HUD official stated, within the St. Louis area, Pruitt-Igoe was meant to “convey blackness, crime, poverty and failure” (United States of America vs the City of Black Jack). Since the middle of the 1960s, suburban St. Louisans had been reading newspaper story after newspaper story, and viewing television news updates, about problems with the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex. Although the local newspapers did provide a reasonable amount of in-depth reporting about the development’s underlying structural problems—primarily high levels of vacancy and a dwindling maintenance budget—as well as discussion of tenant activism and dissatisfaction, much of the coverage still conflated the physical deterioration of the complex with the residents. A 1965 article from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, for example, was intended to explore the problems of the complex in the context of a planned $7 million upgrade, funded by the federal government. But it leads with a lurid description of the buildings’ physical problems. “The image of Pruitt-Igoe is one of crime, vandalism and anti-social behavior […]. The buildings themselves are formidable, rising above the surrounding slums like huge fortresses. The lawns are trampled and littered with glass. Inside, the corridor walls are unpainted and scrawl-covered, giving the impression of age and decay” (Olson 42). The pictures that accompany the article only show the physical issues: vandalism, lack of maintenance, poor design. There are no interviews or discussions with residents, only a cold accounting of the numbers: “This is home for 10,736 individuals, including 7,523 youths (under 21 years old), 2,223 adult females and only 990 adult males. Of the 2,100 families, 1100 are receiving welfare payments. The median annual income is $2,300” (Olson 43).

This was one of the more sensationalistic articles in the local papers about Pruitt-Igoe, but it fits a familiar pattern. Physical issues with the complex were always emphasized, and there were rarely any discussions with residents about their experiences or perspective. Moreover, the issues with the complex appeared to be intractable, with each new local or federal investigation and proposal never really solving the problem. Combined with often sensationalistic coverage of an increasing fear of crime in the city, stories about Pruitt-Igoe were an important part of an emerging racial and spatial script for many White St. Louisans that conflated the general problems facing the city of St. Louis with the specific challenges of Pruitt-Igoe and blamed them both, either directly or indirectly, on the Black poor.

The most recent generation of scholars have worked hard to dispel the “myths” of Pruitt-Igoe in particular, and American public housing in general, by showing that despite a few high-profile failures, there are still thousands of successful projects in the United States that have provided affordable and safe housing for millions of Americans. Those high-rise projects that became well-known for all of their problems, like Pruitt-Igoe, were the victims of design and planning mistakes, poor management, and social and economic forces far outside of the control of the residents (Hunt). Despite this convincing scholarly revisionism, these preconceptions about public housing in the United States remain powerful. And although many scholars point to the architectural and social critics of the 1960s and 1970s as the source of many of these myths, they were just as strong among White suburbanites and, in their hands, became powerful tools of racial discrimination (Bloom et al.).

By 1970, the residents of Black Jack were able to argue that no matter the design of the project, the target population, rent and income requirements, or tenant screening, any type of public or subsidized housing would bring Black people to the suburbs and thus transplant the problems of the city to their bucolic community. The threat was not of Black people per se, as Mayor Barbero and others interviewed by the media put it, but of the Black urban poor and working classes and the institutions it was believed they used and depended on, such as subsidized housing, apartments, and public transit. “If you bring low-income housing out here the same thing will happen that’s happening in St. Louis City. There will be crime and armed robberies and everything else,” a local official said (Wilson). The public institutions of the city would bring the disorder and insecurity of the city. This was counterposed against suburban life, which was secure, peaceful, and privatized, completely automobile-dependent, and relied exclusively on single-family homes (United States of America vs the City of Black Jack 20-22).

The construction of this contrast by Park View Heights opponents, and with it the attempt to reinforce the unstable boundary between city and suburb, shows how suburbanites were working to reconstruct metropolitan racism during this period. On one level, it contained aspects of color-blind, assimilationist politics that did allow certain middle-class African Americans, like Oscar Williams, who were well-educated, successful, and prosperous enough to afford the single-family home, access to the suburbs. But it still associated urban African Americans in general with poverty, crime, and general social dysfunction and sought to prevent their presence in the suburbs. This manifested itself most notably in opposition to all forms of public housing, fomenting battles that would rage all over America from the 1970s onward, as suburban municipalities fought efforts by central cities and the federal government to enforce fair housing legislation and create metropolitan-wide, “scattered site” public housing, including in St. Louis. “It is clear that HUD has arbitrarily established itself as the great social master planner and has determined there will, at random, be subsidized housing projects in stable neighborhoods regardless of the destructive consequences on those neighborhoods,” St. Louis County Supervisor Gene McNary told the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1979, in response to pressure from the federal government that if the county wanted more public money for infrastructure projects (in the form of Community Development Block Grants), then it needed to provide more subsidized housing (Lucken). McNary struck a tone similar to those of Black Jack residents a decade earlier, who saw public housing as a destabilizing, disruptive force in the suburbs. Around St. Louis and across the country, many suburbs enacted strict zoning codes, making it all but impossible to build apartment complexes and other types of multiple-family dwellings (Dreier et al.). Public transportation became similarly off-limits, with many of the campaigns against extending subway or light rail lines to the metropolitan fringe, or even just subsidizing increased bus service, taking on an anti-urban and racial tone (Schmidt).

In many communities, however, fighting to keep out the city and African Americans became a losing battle. The U.S. Court of Appeals struck down the Black Jack zoning ordinance in 1974. In an important precedent, the court ruled that it was not just discriminatory intent that was illegal, but also discriminatory results. “Effect, and not motivation, is the touchstone, in part because clever men may easily conceal their motivations, but more importantly, ‘because whatever our law was once, we now firmly recognize that the arbitrary quality of thoughtlessness can be as disastrous and unfair to private rights and the public interest as the perversity of a willful scheme’” (United States v. City of Black Jack, Missouri). The victory, however, was a hollow one. At this point, construction costs had ballooned to the point that the ICUA could no longer afford the project. Not wanting to let the city off the hook for its lack of public housing, the ICUA worked with the local branch of the American Civil Liberties Union to file another suit seeking damages, and to force the city to allow the construction of some sort of subsidized housing. That case dragged on for almost another decade. The City of Black Jack lost in almost every legal venue, and finally agreed to support public housing with a 1982 consent decree, creating an entry-point for the construction of Kendelwood, a subsidized apartment complex virtually identical to Park View Heights in location, design, and intent (Floyd).

By the time that complex opened, the racial landscape of St. Louis County, and especially the north side of the county, was beginning to change. The efforts of the ICUA and the ACLU to hold the City of Black Jack accountable for providing equitable and affordable housing were not isolated. St. Louis’s open housing movement was vigorous in working to open up housing opportunities for African Americans across the metropolitan region, and they were especially effective in the northern part of St. Louis County, where the Black population of many communities increased significantly in the twenty years after Black Jack incorporated (Heathcott). This success was also driven by demand. Middle- and working-class African Americans were fleeing the rapidly degrading housing stock of central St. Louis for better, safer housing opportunities in the suburbs. When faced with more Black neighbors, the answer for many White Black Jack residents was not to stay, further developing the “beautifully integrated community” that Barbero had celebrated in 1970, but to flee, further and further west along I-70, deep into St. Charles County. During the 1990s and early 2000s, St. Charles was one of the fastest-growing counties in the United States. Some of this was in-migration from outside the region, but much of it was from within greater metropolitan St. Louis, as North St. Louis County became ground zero for a second wave of White flight. By 2010, St. Charles County, which had more than doubled in size in the previous thirty years, was about ninety-six percent White (United States. Census Bureau). Black Jack, like many of the surrounding communities in northern St. Louis County, was more than eighty percent African American. The segregated landscape of seventy-five years ago has recreated itself across the sprawling I-70 corridor, along with corresponding wealth inequality (Lichter et al.). As of 2018, the poverty rate for St. Charles County was only five percent, while it was twice as high in St. Louis County, and even higher in the north county cities like Ferguson, where one in four residents lived below the poverty line (Kneebone).

To Whites in Black Jack, the boundary between St. Louis County and St. Louis City, between city and suburb, had been physical, and inviolate, for the previous two decades, dividing Black and White, poor and middle class, social disorder and social harmony. When the ICUA, with the assistance of federal housing programs and civil rights laws, attempted to dismantle that boundary, Black Jack residents fought bitterly to maintain it by constructing the city as not just a physical jurisdiction, but as a set of physical institutions, particularly higher-density public housing. Bringing public housing to the suburbs, although seen by its proponents as an opportunity to improve the life conditions of complex residents, was thus viewed by suburbanites as bringing the problems of the city to the suburbs. In the decades that followed, suburban Whites across the United States would continue to defend these boundaries by fighting against particular institutions and forms of infrastructure that were considered “urban”—public housing, apartment complexes, public transit—because they would bring with them Black people, and thus the crime, drugs, and general social disorder of the city.

The results of these battles have been devastating, especially for African Americans, American cities, and the global climate. Suburban hostility to the city—both to urban residents and to urban institutions—has been one of the bedrocks of modern American conservatism, and even certain strains of centrist liberalism. The result has been the continuous strangling of resources for anything that would improve the lives of city residents, and a simultaneous boom in funding for the institutions of oppression, particularly policing, jails, and prisons. In response, many city residents continue to look to the suburbs for better schools, housing, and safer neighborhoods, draining resources from the city even further. With the cross burning, rock throwing, and violence of earlier periods no longer socially acceptable, White suburbanites resorted to different legal methods to try and achieve suburban segregation. This included fighting public housing and public transit in the courts and using zoning to limit the construction of apartments and other more affordable housing opportunities. When these methods failed, or were not considered effective enough, White suburbanites retreated to more distant exurbs, exacerbating sprawl and further entrenching America’s car-dependent, energy-intensive urban landscape.

Works Consulted

“CoolClimate Maps.” CoolClimate. CoolClimate Network, n. d. Web. 06. Aug. 2020. https://coolclimate.org/maps.

“Housing Discrimination Suits / Black Jack, Missouri.” CBS Evening News, CBS. Vanderbilt Television News Archive. 15 June 1971. Web. Jan. 23, 2019. https://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/broadcasts/217394.

Kneebone, Elizabeth. “Ferguson, Mo. Emblematic of Growing Suburban Poverty.” Brookings. The Brookings Institution, 15. Aug. 2014. Web. 1 Dec. 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2014/08/15/ferguson-mo-emblematic-of-growing-suburban-poverty/.

Moore, Doug. “Poverty Rate Drops in St. Louis City but the Region Sees No Improvement.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis Post Dispatch, 13 Sept. 2018. Web. 16 Nov. 2019. https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/metro/poverty-rate-drops-in-st-louis-city-but-the-region/article_c965c307-4c49-542b-a90b-80bf807123ed.html.

Schmidt, William E., “Racial Roadblock Seen in Atlanta Transit System.” New York Times. The New York Times Company, 22 July 1987. Web. 14 Oct. 2017. http://www.nytimes.com/1987/07/22/us/racial-roadblock-seen-in-atlanta-transit-system.html.

United States. Census Bureau. “Decennial Census of Population and Housing.” United States Bureau of the Census, n. d. Web. 15 June 2019. https://www.census.gov/prod/www/decennial.html.

United States. Government Accountability Office. “Section 236 Rental Housing: An Evaluation with Lessons for the Future.” U.S. Government Accountability Office, Jan. 1978. Web. 10 Jan. 2018. https://www.gao.gov/products/PAD-78-13.